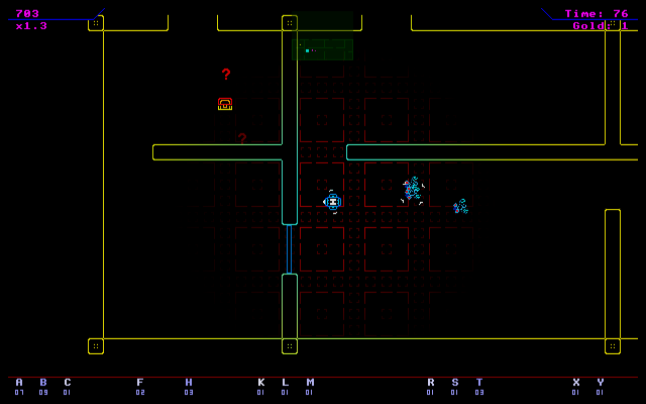

Rejecting Black Boxes: Or - 'Punk Approaches to A.I. and Navigation for Indie Developers'10/23/2015 Introduction of Manifest Pomposity Far back in the mists of time, when games were a new thing, and nobody knew what they were doing, before 'best practices', 'accepted algorithms' and 'standard toolsets' and 'weird sets of words in quotes for no good reason', people were making some amazing games. Download Mame and - after deleting all but about 20 of the quadrillion games it comes with - you'll see that what you're left with is A-MAZING. No, really. In those days, developers looked at their game's requirements and developed exactly what they needed. Nothing more, nothing less. Today, many developers solve their problems by putting together a gigantic lego-stack of black-boxed rendering, physics and A.I./Navigation technology, believing there is no reasonable alternative. I'm going to suggest that there are alternatives to this approach. I'll focus on Spellrazor's A.I. in particular, and hopefully make you consider whether middleware, A* or State Machines are really necessary in your case. A Butterfly's Inner World: Or 'Random Fable Anecdote' In Fable 1 we had pretty little towns and villages filled with complex A.I. behaviour. Try following one person around a village for a full game-day. You'll be impressed at what they get up to. Did you know that villagers get into bed? I don't mean just lie on top of the beds. I mean actually fold back the sheets and get into bed. No? That's because nobody ever went into houses at night because they were locked. Oh, you could break down the door but nobody ever did, and you'd get arrested if you were spotted anyway. We actually discouraged players from seeing it. (Note: we dropped the entire behaviour set for Fable 2, along with many others such as children's school days. Nobody noticed) Earlier in the game's development we found out that the villager A.I. was taking a ridiculous amount of processing time. We added various logs and other debugging tools in order to track down the problem. It was only after someone's careless sword-swing smacked into a butterfly that we understood what was wrong. The butterfly yelled 'Help' and then A* navigated its way to a village exit whereupon it disappeared up a trade-route. Someone had made the default behaviour 'human'. I mention this as an illustration to hilight that 'Best' is not always 'Appropriate', though many would have you believe so. They should be flogged. Gently. With something moist. Spellrazor: Or 'What Does Your Game Actually Need?' Spellrazor is my ridiculous '80s game resurrection project. It's a top-down rogue-lite dungeon shooter for PC and Mac with 27 fire buttons and a host of different enemies. The game goes into a kind of bullet-time when you're in danger, allowing you to use those those 27 spells tactically - even in the midst of a complex firefight. Nono. Ignore the picture. It's not the same as actually playing the game in all its throbbing neon-tinged glory. Just pretend I didn't put the picture up at all. Keep scrolling. Bit more. Stop! That's better. Spellrazor is of the same school of thought as old Williams classics like Robotron and Defender. It's sinister, it's deadly, and its enemies are total bastards. When I started, I had a clear idea of what I wanted game-play to be like. I had a little scenario in my head that I used to test the suitability of anything I wanted to add: "Okay - on the other side of this door there are 3 flies and a security bot. I'm out of [Z]ap, so... Oh! I have a [J]ump! I can hop over the wall and take out the flies, then use a single arrow followed by a [Q]uake to take out the Security! Here we go..." I find this kind of exercise useful to figure out the verbs in the game. In Spellrazor's case 'Panic' actually came up too often, so I changed things around a bit. Anyhow, as you can guess from the description, it's a kind of 'breach and clear' game with plenty of opportunity for things to go horribly wrong. For this scenario to work, I required three things:

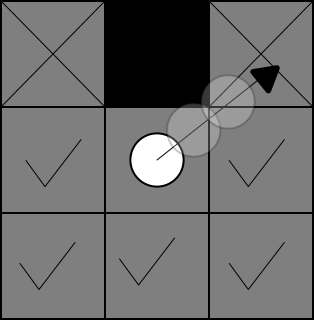

Embracing Retro Simplicity: Or 'Zelda's Artificial Stupidity' Seeing as I was in an 80s mindset, I didn't want to use A.I. that led to perfect behaviour. I wanted the retro feel to permeate right through the game - after all, the low-tech approach was good enough for some of the best games ever made: Defender and Robotron. So it should be good enough for me, right? But wait! Some of you are thinking 'Those games were really primitive! There's no justification for that kind of tech now, in 2015'. Okay, so how about Zelda? If you've played any Zelda game since Link to the Past, you have probably been impressed by the puzzle design, dungeon design, overall 'feel'. But what about the A.I.? Can you remember being hit by an enemy other than a boss in Zelda? No? That's because they were games designed to make you feel good when Link hit or blocked an enemy and not the other way round. The last thing you want in a heroic quest is artificial intelligence that allows enemies to defeat you. If anything, heroic games require artificial stupidity; enemies arranging themselves to create the best, most heroic narrative possible, only providing the illusion of intelligence and some kind of understandable risk-reward. Remember the butterfly? Not that. See - I promised it would be relevant. Most A.I. tutorials seem to work from the Platonic idea of creating perfection in pathfinding and logic (in the form of 'A*' and Finite State Machines) with the assumption that you can always work back from this in order to create personality/flaws. While a perfectly usable approach, it isn't necessary, and is potentially an over-engineered solution for the problems of your game. I'm going to illustrate this by describing the behaviour of a couple of Spellrazor's units. Spellrazor: Or 'Using Map Generation to Your Advantage' Spellrazor has a hierarchy of navigation. 1) Room/Door-based: moving between neighbouring rooms using doorways as targets 2) Tile/node based: moving from grid-square to grid-square at high or low granularity 3) Physics: acceleration, velocity and inertia Using 1) requires 2) and 3), using 2) requires 3), and 3) can be used by itself. Paired with some simple behaviours, this is sufficient to create enemies that are satisfying to engage with in Spellrazor Creatures have 3 notions: TargetPosition, GoalPosition, and - rarely - a Sidestep direction.

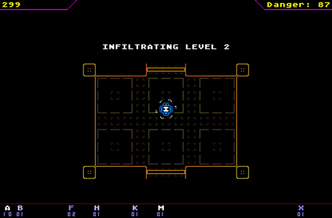

After creation, my map hierarchy is:

I'll now show how this information is used to elicit the appropriate behaviour for 3 enemies. Fly - Physics Based Navigation Only The fly is the simpest of the enemies. It is a little homing missile. It uses no navigation information at all. The fly's behaviour is:

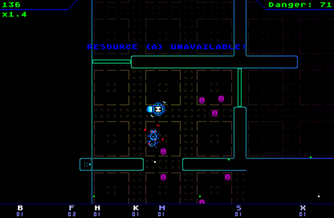

Flies tend to bunch up quite a lot and slide around corners (look at the original pic of Spellrazor). These swarms break up a little in open spaces due to the random angle osciallation. This is a good thing. It feels right. Flies are fairly lethal as they are fast and tend to arrive in groups (which form due to their behaviour rather than intelligent placement or other algorithmic flocking). Despite their simplicity, flies are satisfying to kill because players need to precisely control their positioning in order to accurately target them. Swordsman - Tile Based Navigation The swordsman is one of few enemies that require more than one hit to kill. It is also one of the deadliest, despite having no real notion of where it is in the map. However, because this game focuses on players hunting down enemies, this lack of intelligence doesn't matter. The Swordsman's behaviour is:

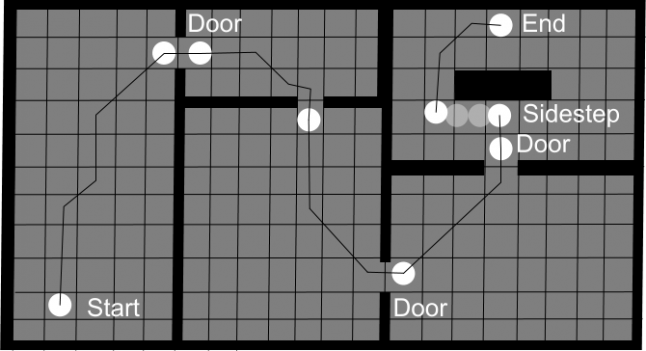

Security - A Classic Navigator? The Security bot is, by far, the nastiest enemy in the game. It teleports into the corner of the target's room, and once it has arrived, it follows the target mercilessly, belching out hundreds of bullets once in range. It is really nasty. It is also the most complex A.I./Navigator. "Oho!" I hear you cry. Because you are an Edwardian gentleman. "Oho! I spy a case for complex navigation, perhaps even A*? You are bested!" I'm sorry, Mr Mutton Chops. This is a punk article about punk coding. Take your weird elephant's foot umbrella stand, grab an absinthe and shush. The above diagram is definitely not drawn in crayon. It does, however, illustrate the route and decision points of the Security bot, and how it gets between them.

Despite the apparent complexity, its rules are fairly simple:

Now, because blockages are never dead-ends and the map is relatively simple (rectangular rooms with big chunks taken out of them to add detail) this simple behaviour results in a devastatingly smart foe. It tracks you across the entire map, yet only rarely does it think about anything other than the nodes immediately around it. Even when it does have to do a search, it's a breadth-first search of around 30 rooms and thus close to instantaneous. You'll notice that even with this creature, there is no state-machine! The only extra detail recorded is the Sidestep direction. Conclusion At no point have I wished any of my enemies were smarter or more complex in their behaviour. Spellrazor isn't 'The Last of Us.' I'm not trying to convince the world that my little robots are people. They're not. They are dangerous little robots. They are predictable when necessary, and each requires very different approaches when encountered. These are what Spellrazor needed, not what was proscribed by someone else's vision for another game entirely. A Final Odd Music Analogy I love early electronic music. I have a particular fondness for the work of Louis and Bebe Barron on the Forbidden Planet soundtrack. The Barrons didn't have an orchestra or synthesizer at their disposal. Instead, they fashioned small, flawed circuits that often burned out while recording. They warbled, they whooped, they sputtered and crowed and nobody had ever heard anything like it. I feel we've an opportunity to do the same thing now. The imperfections and flaws in our algorithms are part of our games' personalities and key to the punk developer spirit. If Johnny Rotten could actually sing, the Sex Pistols would have been just another pop group. Our flaws should be embraced by ditching black boxes and actually learning to do stuff ourselves; messily, clumsily, but originally. ...if it's right for the game... Spellrazor can be downloaded for free at: http://dene.itch.io/spellrazor Dene Carter can be found on Twitter as @Fluttermind

13 Comments

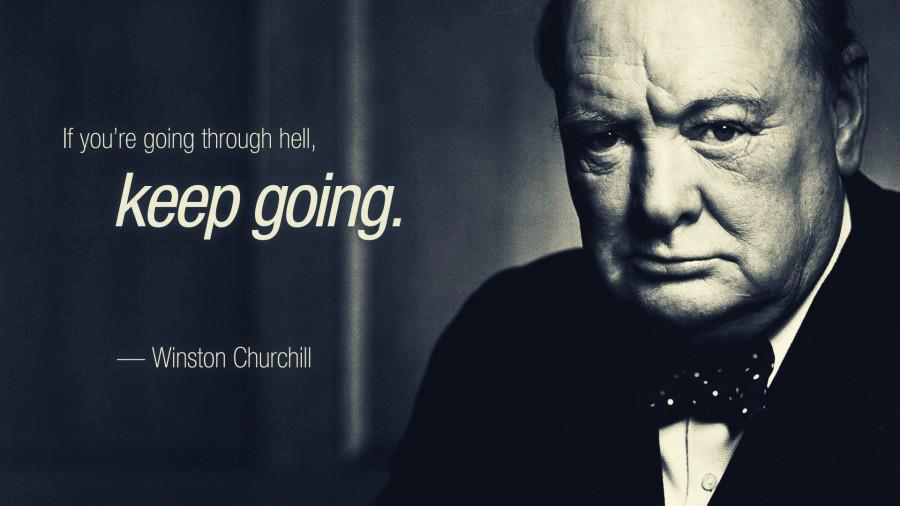

Those who know me are aware that BeMuse has been slowly driving me mad over the last few months - if not longer. I'm not happy with the way the gameplay clashes with the visuals. I'm not comfortable with the non-tactile movement. I'm concerned that I've ended up with a one-shot 'experiential' game despite stating that I'd never do that again after Incoboto. Every day, booting up Unity takes a little more out of me, and each evening leaves me feeling like I've heard the gears of the infernal realm grind away my resolve. To overstretch the metaphor, it's been hell-ish*. *Note: 'ish' because real hell probably doesn't involve being an indie game dev with sufficient food, a house in the Bay Area, and people who care about him. There's a Winson Churchill quote I'd like to use here: I've seen this quote used by people working on long, difficult projects. I've seen it used by indie developers. When times are tough, money is tight, or a set of mechanics aren't working out, it rises up once more to provide an inspirational push. "Just a bit further and you'll reach it!" "Come on, all that stands between you and success is hard work!" "It's tough, but it'll be worth it!" But there's a problem. While its 'man up' message is useful where one merely needs to grind toward a (hopefully inevitable and positive) conclusion it's a terrible mantra for doubt-ridden, uncertain creative work. Yet I'm guessing even now that some young indie has this as their backdrop, reminding them that if things aren't working out, they should merely keep digging that hole they are in a little deeper in order to strike gold. Hell and 1% Inspiration As the 'hole' comment above illustrates, there are other variants,such as: "Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration" This, too, suggests that sheer hard work and determination will pay off. You're supposed to read: "Even geniuses need to work hard for their ideas to come to fruition, so you work hard, too, and you're 99% there." Apparently, difficulties merely need sufficient grinding of teeth in order to turn into success - or at least to make way for another 'Genius 1%' moment to pop in. In truth, the 'Genius 1%' may pop in and out throughout a project. Sometimes a new 1% pops in and points out that part of the other 99% of work you were doing was really stupid and pointless. Sometimes a 1% will pop in and lie about how cool and successful it is, eventually revealing itself to be just an additional '99% of perspiration' in disguise. The problem is that they all look the same, so it's often hard to be sure which is which, and when the time for hard work alone has come. The AAA Mindset So how does AAA cope with the variability of the 1% Genius element? It doesn't. It does its very best to eliminate the vagaries of the 1% and pushes that 99% to a full, hearty, knowable 100% of perspiration (Keep Going!). A modern AAA studio's continued existence relies on getting rid of that tricksy percentile. This is understandable, because for them, the fail-state is unthinkable; publisher cancellation and, after some fraught months, a purge of the entire team. I've worked at AAA companies for decades and this kind of thinking rubs off on you even if you don't realise it. Like many, I've been trained to believe that every project is a marathon... run at the speed of a sprint, or at least a wild, sweaty jog. "Working damned long and hard is the only way to make something successful. Failure isn't an option." My previous game, Incoboto, was built with this philosophy. It was successful, reviewed very well, and was largely a work fashioned by grinding my way through an enormous workload, entirely by myself, in isolation, over a 22 month period. I was incredibly pleased with the results, but it reinforced the wrong-headed lessons I outlined above. Embracing the Indie Mindset (finally) 'Real' indies don't think this way. Indies often haven't learned the big, adult lesson about grind and grit. They mostly expect to fail in one way or another. And when they do, they shrug it off and move on. Even those agonising over a game for years are usually fairly sure their game works in principle even if it isn't perfect. They've already thrown away more good ideas than I've had published games and that's okay. As an indie developer, what should I have learned instead of my big AAA lessons? Well, here are 3 off the top of my head:

So, having admitted that I've learned some bad lessons, and finally realised what the correct lesson are, how am I planning to change things? Well, this comes in two parts. Spellrazor A couple of weeks ago, my wife was required to attend a work event in Mexico. It was horribly hot and humid, so - as a massive introvert - I decided to hide out in the air-conditioned hotel room for the 4 days we were there. During that time, I worked on a weird old game I've considered reviving for many years. It's called 'Spellrazor'* *yes, it's a deliberately cheesy title - as befits a child of the 1980s The cabinet blurb would be: "Spellrazor marries the procedural generation and permadeath of rogue with the visuals, tactile feel and action of games like Robotron, Defender and Berzerk." "It's a roguelike shooter with 26 weapon buttons. Each key on the keyboard represents a spell. You kill things, you collect spells (in the form of letters) and you can use these at any time by pressing the appropriate key." When I was about 12, I saw Defender and fell in love. In its brightly pixelled worlds I discerned a future filled with delight and wonder. I have a particular love of games from this period (1980-1983). They were frequently cold, cruel and utterly uncompromising. Spellrazor is a game from the same school of philosophy. I released versions online last week, and friends of mine are already playing it. Early signs are really good. Unlike BeMuse, there's no requirement of secrecy or of confused players trying to figure out 'what the hell kind of game is this?'

For those patient enough to have waded their way through this little post, you can follow Spellrazor (and play early builds) on Tigsource here: http://forums.tigsource.com/index.php?topic=50678.msg1184968#msg1184968 BeMuse For now, BeMuse is going on a shelf. I don't think it's permanent. I hope to return to it at some point in the future, with the verve, joy and speed of progress I'm experiencing with Spellrazor. In the meantime, if anyone is interested in playing the weird text-heavy skeleton (not the graphical game) of BeMuse, please contact me and I'll be more than happy to share. Thanks for your time, and for your interest. |

AuthorFluttermind’s director, Dene Carter, is a games industry veteran of over 25 years, and co-founder of Big Blue Box Studios, creators of the Fable franchise for the XBox and XBox 360. Archives

April 2022

Categories |